The Transformative Community

Transforming Our Narrative for These Times

The organizational or core story

In his last speech to Parliament, Winston Churchill talked not about politics but spirit. “Spirit is what lies beyond our senses, thoughts, and feelings. Spirit is pure. Spirit is tranquil. Spirit is in harmony with truth… this is the essence of humanity – your true self or what I am calling your Inner Core” (Wadhwa 36). Churchill understood that an organization’s capacity to have an impact is rooted in its core corporate narrative. The collective meaning experienced in the fundamental core is rooted in its mission, vision, and values. When simultaneously a group is faithful to this aspirational call, the world experiences them as having integrity and authenticity. Hitendra W Wadhwa, in his book Inner Mastery and Outer Impact, states, "At the very center of the sun is what scientists call its

core. The core represents only 1 percent of the sun's volume. Remarkably, this 1 percent is responsible for 99 percent of the energy the sun generates" (1). Similarly, an organization's core is often under-appreciated and yet motivates and implores service excellence to impact the world. The narrative or organizational story expresses the central core in words and symbols that touch every member's heart.

The organizational story embodies the essence both within and beyond the group. This narrative fosters identity, purpose, and belonging, calling forth the group’s deepest aspirations.

The narrative offers a collective compass in historical moments of rapid and continual change. Contemporary organizations and societies have seen and continue to see several significant shifts:

-

From tribalism to interculturalism

-

From individualism to interdependence

-

From silos to collaboration

-

From human-centric only to eco-centric, connecting with all of God's creation on earth and in the universe

These shifts raise societal questions requiring groups to reevaluate and shape a new narrative.

Organizations struggle to understand and make these concepts real as they become open to increasing diversity, cooperation, and collaborative relationships. Thus, every group is invited to explore their assumptions, beliefs, and understanding of the world. This self-reflection allows the group to reimagine their narrative for a time of emergence.

Any direction or narrative must appreciate the connection between the various global crises. As Pope Francis said in Laudato Si: “It cannot be emphasized enough how everything is Interconnected (93). Laudato Si, helps us understand that we cannot segregate issues such as climate crisis, racism, immigration, inequality, and others into isolated or neat compartments. Instead, new opportunities emerge through exploration based on their interrelatedness.

Today’s contemporary questions ask groups to reshape their core narrative as they seek to participate in an evolving world. Religious communities are not immune to the process of change. They, like all groups, must examine how their core beliefs and practices meet the world's needs. It means being open to a continual change process with new questions and challenges that significantly shape our society's future

The Transformative Process

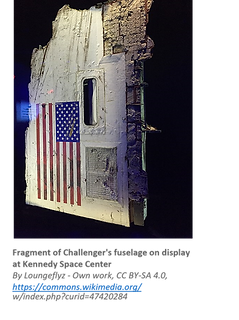

As the world becomes more interconnected, the group messaging must be congruent with its core within and beyond. For example, each time we send individuals to space, we remember the spacecraft Challenger that blew up at launch. The challenger is an excellent example of the lack of organizational congruence. The creators and designers espoused one set of practices that lacked congruency with their practice. The flight had tremendous social pressure to launch because the first American civilian, a teacher, was on board to participate in the Teacher in Space project. In 1984, President Ronald Reagan launched this program to inspire and honor teachers and spur interest in mathematics, science, and space exploration. This background played a role in creating the circumstance that led to the lack of congruency between the espoused norms and norms in use.

The challenge for any group is transparency and the openness to reflect on what it espouses and how it acts. Often there are discrepancies between these two realities. It takes continual discernment to link our espoused message with the practice. An unaligned narrative that expresses our core can lead to a lack of integrity and public credibility. This reality became a reality with the tragic explosion of the Challenger.

We have learned from studies on collective trauma that, when denied, the past impacts current reality. For example, the American story continues to be impacted by discrimination and negation of the indigenous and black people. Yet, we tell ourselves that we have elected a Black President and Vice-President; therefore, discrimination no longer exists. Every group, society, and organization has wounds often repressed that often silently impact their current narrative and identity. Again, it speaks to the espoused values not followed with the appropriate action.

Furthermore, the awareness and exploration of unresolved collective issues are crucial to a group integrating its past, present, and future. The past creates identity; the present speaks to the moment and the future offers aspirations and dreams. The group must commit to a continual process of seeing the narrative not as static but evolving that aligns with the core purpose. This ongoing discernment links the group's current espoused belief with the reality that establishes collective meaning.

We live in an era where technological advances offer new ways of telling our stories. The use of apps establishes new mediums for sharing our core with larger audiences. For many of us, that shift is an adjustment, whereas it is the norm for younger generations. These shifts will only expand and grow, offering more expansive ways to share one’s story.

The gospels speak to the adaptation of a narrative. With the death of Jesus, his followers struggled to form their core message. Since Jesus was no longer physically present, the apostles became the gospel's storytellers. The Acts of the Apostles depicts Jesus's followers, creating a narrative that remains rooted in Jesus's teaching yet speaks to their contemporary audience. The story of the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus in both the Gospels and Acts illuminates how they reimagine their cultural narrative as appropriate for their emerging reality. Today, like the apostles, a group’s challenge is to adapt its core to a new era with new tools.

The contemporary technological developments and example of the Acts of the Apostle speak to the constantly evolving methods of communication. The challenge for any organization or group is to affirm and renew their stories to engage with the unique current social issues. They must embody the wisdom of their historical story while opening themselves to exploring it for an unfolding future. This process demands a grounded contemplative presence to enter this dimension of integration.

Elements of the Core Story

Every organizational story includes three essential elements: the presence of a collective story, the integration of past successes and the reconciliation of past failures, and the ability to adapt the narrative to changing times. These interwoven elements guide the development and expression of their core.

Presence of a Collective Story

Lao Tzu speaks about presence in a profound yet simple, understandable way:

Watch your thoughts,

they become words

Watch your words, they become actions

Watch your actions, they become habits

Watch your habits, they become character

Watch your character, they become your destiny. (Lao Tzu)

A group's narrative should align with this advice. When these traits are connected, the narrative expresses the group's authenticity within and outside the community.

In Healing Collective Trauma, Thomas Hubl cites Otto Scharmer's definition of presencing:

“Presencing is based on an inner change of location. Presencing means liberating one's perception from the "prism" of the past and letting it operate from the field of the future. That means that you literally shift the place from which your perception operates to another vantage point. In practical terms, presencing means that you let it come into the present.” (90)

When we reflect on a group narrative, we must avoid becoming stuck in the present or focused primarily on the future. The group needs to explore the past's impact; it will continue to shape the present as the group pursues the future.

A challenge is to hold the present, not succumb to the past or look beyond the moment to the future. The collective story centered on the present allows the members to hold sacred their past and engage in foreseeing the future. It is a creative and energizing process of holding the organization's center point journey through time.

Presence also means recognizing the group's individual and collective story woven together. Daniel Christian Wahl quotes Mary Oliver in Designing Generative Cultures, "to pay attention that is our endless proper work" (163). Mary Oliver's phrase speaks to the ongoing spiritual energy needed to remain rooted in the collective narrative that spans the three passages of time.

The institutional collective story allows us to reconcile the past with the present in a way that integrates past failures that could unintentionally impact the present. We tend to exalt the positive dimension and avoid the painful parts of our history. How often have we read about institutions that, when exploring the future, became stuck in the past, afraid to risk their current success? Their inner story often keeps them from risking and accepting the unknown as they move into the future.

The communal faith journey includes dealing with the woundedness of the individual and the community. In Ariell Burgers book, Witness: Lessons from Elie Wiesel's Classroom, Elie Wiesel claims: “Kierkegaard wrote that faith must be lost and found again." Wiesel replaced the word "lost" with “wounded.” He says: "At one point in life, we must be wounded to be true. One Hasidic master said, 'No heart is as whole as a broken heart.' I believe that no faith is as whole as a wounded faith" (8). Transformative communities actively engage in the communal, spiritual journey of exploring and integrating into their story, the wounds of their past.

In exploring our story, we need open and receptive hearts able to see objective truth honestly. Every community's story becomes interwoven with moments of pride and regret. For example, the speed with which the United States was able to produce a vaccine for COVID is a source of pride while at the same time there is regret over the disenfranchising of Indigenous and black people. Likewise there is pride over the level of goods services we are able to produce and regret over the neglect and lack of caring for our planet. More recently, it has been reported that our country has a practice of accepting immigrants from Mexico and South America but then separating families placing children in camps. In this way, we espouse one virtue, a land of immigrants, while at the same time we exhibit the opposite. This is the narrative that forms our collective soul.

It takes vulnerability to explore the light and shadow of the collective. For group transformation, we must hold in tension the contradictions of our past sins and our gifts. Brene Brown, in Daring Greatly, offers this lens on vulnerability. “Vulnerability is not weakness, and the uncertainty, risk, and emotional exposure we face every day are not optional. Our only choice is a question of engagement. Our willingness to own and engage our vulnerability determines the depth of courage and the clarity of purpose…” (2). In telling our story, we risk being vulnerable to public criticism and nasty comments by sharing the less-than-perfect parts of history. Only by the heartfelt embracing of these parts can we shape the world. We must continually reconcile internally and externally the collective beauty and wounds within our historical narrative.

Thomas Hubl talks about the importance of healing our past historical narratives.

He notes:

Pope Francis states in Laudato Si that "Intergenerational Solidarity is not optional, but rather a fundamental question of justice, since the world we have received also belongs to those who will follow us “(106). Each generation is called to deepen and renew the group story for their historical time. If they become stuck or resist God's invitation, the narrative and vision become stale and lack meaning and purpose.

Adaptation of the Narrative

According to Alan Seale, in Create A World that Works, Buckminster Fuller said: “ You never change things by fighting the existing reality, build a new model that makes the existing model absolute” (171). That is the power of adapting the narrative to the times; it allows one to enter into the co-creative process of shifting the group’s attention to the unfolding historical moment.

One of society's profound experiences was adapting the narrative about the presence of God. For many, God was a person out there beyond us. Neil Armstrong's landing on the moon offered a greater conscious awareness of God. It began a lifelong journey for many to see God in all of life, thus creating an expanded vastness and appreciation of God

The group's tendency in challenging times is to create an either-or scenario. During these moments, the collective tends to focus on the limitations or abundance. This either-or-reflection tends to create a stuck narrative. It is vital to hold both traits in tension. These two realities seem like opposites. Yet, a group's future depends on accepting and defining the current limitations while embracing the abundance of possibilities often unseen.

Potential = an energetic essence; waiting to take form; what wants to happen.

Possibility = a form that the potential might take in the physical realm taking a specific form; what could happen

Outcome = the form has taken shape and become ‘real” in the physical realm; what did happen (176).

The group establishes the foundation for creating an energizing narrative through living in the present, reconciling the past, and adapting to the emerging future. The openness of embracing the emerging future opens the group to explore new ideas, methods, and models, allowing groups to grow into their new worldview expressed through stories. Alan Seale offers a roadmap for creating a compelling new narrative. He invites us to see potential, possibility, and outcome in the new.

Summary

Alan Seale cites Stephanie Page Marshall, who claims:

We cannot underestimate our individual and collective power to consciously “provoke” our system's transformation in the direction we desire; shared intention and collective purpose drive system innovation and transformation (155).

A powerful narrative moves the group to exceed their wildest imagination. Marshall’s comment speaks to the power of presence, reconciling and adapting the narrative to the times. These three principles allow the group to continue co-creating with God for their generational time. God's invitation to every group to create a story around their core thrusts them into participating in the co-creative process of these shifting times.

A group narrative is crucial because it describes why we exist, our hope for the future, and the values guiding our internal and external relationships. The inner passion of our story guides and motivates us to be instruments of change for an evolving world.

In the Book of Hope, Jane Goodall states, “Hope is what enables us to keep going in the face of diversity. It is what we desire to happen, but we must be prepared to work hard to make it so” (8). The narrative tells the story of our hope for a more just world.

The narrative that captures these three elements can energize communities as they move into the future. When a group reflects on this framework, it allows them to see their potential and what is possible and achieve an outcome beyond their initial dreams.

About the Author

Mark Clarke

This article is by Mark Clarke, a Senior Consultant for CommunityWorks, Inc. He is available for consultation and welcomes a conversation to discuss your thoughts and questions about his writings.

For more information about using his article and concepts, please contact him at mark_5777@msn.com or calling 616-550-0083.